- March 13, 2018

- 599

Wołkonowski: Polish high school graduates receive fewer “student baskets”

In Lithuania, there is a chain of Polish-language state schools, consisting of 40 junior high schools and high schools, in which each year between 2010-2017 around 1000 high school graduates students passed matura exams. The aim of the article is to examine the level of admission to higher studies in Lithuanian high school-age secondary school graduates through the “student basket” in comparison to the national average. This new model of higher education in Lithuania was introduced in 2009. In the article, data from the national recruitment system will show not only the level of Polish-language education in Lithuania compared to the national average, but also the level of Polish-language junior high schools. .

Higher education reform – “student basket”

Political and economic transformation in Lithuania in the early 1990s has affected a wide range of life in the country’s society. Free-market mechanisms that were introduced into the national economy were also implemented in the sphere of higher education – at first there was a division into university and colleges, and next to state-owned universities, private appeared.

To introduce the free market competitiveness mechanism in 2009, the system of financing higher education was changed by introducing the “student basket”. The meaning of the new model was basically money for the student – the “student basket” contained all the costs of studies (remuneration of lecturers and administrative and technical employees, research, maintenance of material base, etc.) related to studies for one student of a given field of study over a one-year period.

The number of baskets was set by the Lithuanian government and it oscillated around 47% of the number of high school graduates, which is why a ranking list was also introduced for candidates applying for a “student basket”, which provided free of charge studies. Results of matura at the state level decided which of the candidates would receive a “student basket” (according to the ranking list) – the candidate who was on the “student basket” list had free higher studies, while the candidate who did not receive the “student basket” could join the paid studies – the tuition of such studies was practically equal to the “student basket”. This model also allowed to allocate budgetary funds to non-state higher education institutions, because a student who received a “student basket” made the choice of the university on which he will study – according to the principle of money for a student. In this way, a liberal free-market mechanism of higher education was introduced in Lithuania. The number of baskets and their amount in the field of study allowed the state to correct the stream of students, granting for the directions of a large number of baskets important for the development of the country’s economy, which gave the possibility of free studies for a larger number of people in such majors.

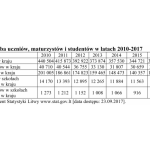

To examine this situation, let us first consider the tendency of the number of “student baskets”.1. The amount of “student baskets”and the number of high school graduates in the period 2010-2017

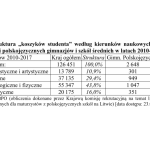

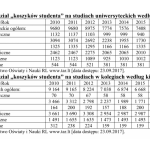

The number of “student baskets” (second row of table 1) and their division into university studies and colleges (third and fourth rows in table 1) was determined by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Lithuania. In the fifth row of table 1 there is the number of high school graduates in the country for each year, in the sixth row – the national average of free higher education with a “student basket” for each year. In the last column of the last row – the average national level for the period 2010 -2017. The next two tables provide data on “student baskets” for university programs.

From the data contained in Tables 2 and 3 we can see a clear tendency of a decreasing number of “student baskets” to the humanities and social sciences and an increase in the number of baskets for physical and technological sciences (from 40.4% from the total in 2010 to 48.3% in 2017 year) both at university and colleges. This tendency will be more visible if we take into account the shrinking number of pupils and high school graduates in country schools, pupils and high school graduates in Polish-language schools and students in the country.

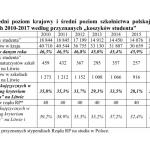

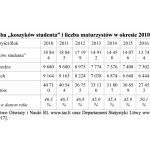

In Table 5, in rows two to four there is data on the number of “student baskets” and the number of high school graduates in the country and the national level of baskets granted in a given year – as we see in recent years increased the level of baskets awarded compared to the number of high school graduates than it was at the beginning period. In the row 5-7, data on the number of “student baskets” were given to high school and Polish-speaking secondary school graduates, the number of high school graduates in these schools and the level of these schools and junior high schools according to the basket criterion.

As we can see from the data in Table 5, the level of baskets granted to high school and junior high school students was always lower than the national level of 10.5 percentage points (hereafter pp) in 2010, to 26.6 pp in 2017, and the difference was upward trend, which is a threat. An important factor is the trips of high school graduates from Polish-language schools and junior high schools to study in Poland from the Polish Government’s scholarship, because these people do not apply for granting them a “student basket” in Lithuania. This was taken into account in the last two rows of Table 5 – as we can see the difference in levels has changed – from 7.6 p.p. in 2011 to 21.9 p.p. in 2017.

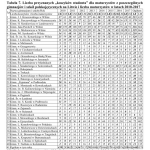

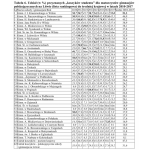

Tables 6 and 7 contain data on the share and number of “student baskets” awarded to high school graduates from Polish-language high schools compared to the national average – this is the ranking of Polish-language education in Lithuania according to the “student basket”.

Analyzing Table 6, we see that only the JI Kraszewski junior high school according to the criterion of the average share of the “student basket” in the analyzed period 2010-2017 had a higher level of 51.3% – than the national average in this period – 47.3%, while in separate years, individual junior high schools exceeded the national average: in 2010 – 6 junior high school (JI Krszewski in Vilnius, K. Parczewski in Niemenczyn, E. Orzeszkowa in Biała Waka, St. Kazimierz in Miedniki, in Rukakowice, J. Slowacki in Bezdany); in 2011 – 6 junior high schools (J.I. Kraszewski in Vilnius, H. Sienkiewicz in Landarów, Wł. Syrokomli in Vilnius, J. Lelewel in Vilnius, High School in Ciechanowiszki, St. Batory in Ławaryszkach); in 2012 – 2 junior high schools (A. Mickiewicza, in Awiżenie); in 2013 – 5 junior high schools (JI Kraszewski in Vilnius, K. Parczewski in Niemenczyn, H. Sienkiewicz in Landwarów, in Rukania, in Pogir); in 2014 – 7 junior high schools (JI Kraszewski in Vilnius, K. Parczewski in Niemenczyn, in Mickunach, in Grzegorzew, in Awiżenki, E. Orzeszkowa in Biała Wace, in Rukojnie); in 2015 – 2 junior high schools ( H. Sienkiewicz in Landwarów, in Mickunach), in 2016 – 2 junior high schools (K. Parczewski in Niemenczyn, A. Mickiewicz in Dziewieniszki); in 2017 – 1 junior high school (JI Kraszewski in Vilnius). Analyzing this data, we notice large fluctuations in the number of “student basket” for each year and for junior high schools. Especially we see it in the case of junior high schools, in which high school graduates were a few or a dozen people.

Table 7 gives data on the awarded “student baskets” and the number of high school-age secondary-school graduates and high school students in the period under consideration. From the table, we can see that in 2010-2017, 8378 secondary school students graduated in Polish-speaking junior high schools and secondary schools, of which 2,648 received a “student basket”, which accounted for 31.6% of all Polish-speaking secondary school-leavers. With the national average (47.3%), the number of “student baskets” is 3963 – this results in a shortage of 1315 baskets for high school-age Polish secondary school graduates.

Table 8 presents data about fields of study selected by people with a “student basket” from Polish-language junior high schools and high schools in 2010-2017.

Analyzing the data from Table 8, we can notice that the structure of the student baskets awarded to secondary school graduates differs from the national structure. The largest differences are in the study fields from social sciences, where the student baskets were awarded more by 6.4 pp, while in the case of the field of study in technological and physical sciences – by 4.3 pp fewer, similarly in the case of biomedical sciences – by 2.7 pp fewer. These differences show the socio-humanist orientation and the weaker level (interest) of the technological and biomedical sciences.

Conclusions

In 2010-2017, Polish high schools and secondary schools in Lithuania held 8378 high school graduates, of whom 2648 received “student baskets”, which provided them with free higher education. This constituted 31.6% of the total number of high school graduates, with the national average of 47.3% in the analyzed period. The difference in levels is 15.7 pp, – this is a shortage of 1315 “student baskets” for high polish secondary-school graduates.

The participation of high school graduates with a “student basket” from lower secondary schools in Lithuania has a decreasing tendency: from 35.8% (national average 46.3%) in 2010 to 27.6% in 2016 (national average 50.1%) . This is a trend that exacerbates the condition of Polish-language education in Lithuania – the difference is deepening between the national average and the level of Polish-language education according to the criterion of the number of “student baskets”. A slight increase in 2017 should be noted, which was caused by the general increase in the number of baskets in the country with a falling number of high school graduates – 28.2% (national average 54.7%) and 26.5 pp difference to the national average.

Of the 40 Polish-language junior high schools and high schools studied, only one, namely the JI Kraszewski junior high school has a better result (51.3%) for the years 2010-2017 than the national average in this period (47.3%). Another two junior high schools (junior high school K. Parczewski in Niemenczyn and junior high school under the name of H. Sienkiewicza in Landwarów) are lower than the national average of 0.4 pp and 2.1 pp – this difference is very small. In separately analyzed years, individual (16) lower secondary schools reached the level of the national average.

Another 4 Polish-language junior high schools according to the ranking list (Lp 4-7) in Tables 6-7, the difference ranges from 8.4 pp to 10 pp – this difference is significant, but in individual years these schools exceeded the country’s average level, by granted “student baskets”.

The declining share of the “student basket” among secondary school graduates of Polish gymnasiums overlaps the period of introducing a unified state language exam in the Lithuanian in 2013.

It should be noted the decreasing number of pupils in schools in Lithuania and Polish-language schools and the drop in the number of students by 37.5% – from 201 thousand and in 2010 to 126 thousand in 2017. This is the result of an erroneous pro-family policy conducted by the Lithuanian authorities – the Parliament and the Government of the Republic of Lithuania. It is necessary to study how many schools have been closed and how many teachers were dismissed due to a wrong family policy.

The structure of “student baskets” of high school and Polish secondary school students differs from the increased share of fields of study in social sciences and humanities, and a reduced share of fields of study in technological and physical and biomedical sciences.

With the falling share of “student baskets” for Polish high school graduates, it will be difficult for the Polish minority to reach the average national level of higher education in Lithuania.

Thanks

The author greets the prof. Pranas Žiliukas president LAMA BPO for sharing data on the number of “student baskets” awarded to graduates of Polish-language junior high schools in Lithuania in 2010-2017.

Summary

In Lithuania, in 2009, a liberal model for financing higher education was introduced based on the “student basket” in accordance with the “money for the student” principle. In accordance with this model, the Lithuanian state, by awarding a “student basket” for a university candidate, awarded free studies to practically half of the high school graduates according to the matriculation criteria. In 2010-2017 (within eight years) Polish high schools and secondary schools in Lithuania graduated 8378 high school graduates, of whom 2648 received “student baskets”, which provided them with free higher education. This constituted 31.6% of the total number of high school graduates, with the national average of 47.3% in the analyzed period. The difference in levels is 15.7 pp, – it is a shortage of 1315 “student baskets”. The participation of high school graduates with a “student basket” from lower secondary schools in Lithuania has a decreasing tendency: from 35.8% (national average 46.3%) in 2010 to 27.6% in 2016 (national average 50.1%). This is a trend that exacerbates the condition of Polish-language education in Lithuania – the difference is deepening between the national average and the level of Polish-language education according to the criterion of the number of “student baskets”. Of the 40 Polish-language junior high schools and high schools, only one, namely the JI Kraszewski junior high school has a better result (51.3%) for the years 2010-2017 than the national average in this period (47.3%). Another two junior high schools (junior high school of K. Parczewski in Niemenczyn and junior high school under the name of H. Sienkiewicza in Landwarów) are lower than the national average of 0.4 pp and 2.1 pp – this difference is very small. In 2010-2017, still 14 junior high schools attained the level of the national average in separate years, however their average level for the analyzed period was lower than the national average in 2010-2017.

This text appeared in print in the Yearbook of the Association of Scientists of Poles in Lithuania, Year 2017, Volume 17, pp. 201-217, more about the Yearbook on http://snpl.lt/rocznikT17.php

Translated by Katarzyna Widlas within the framework of a traineeship programme of the European Foundation of Human Rights, www.efhr.eu.